It’s a book! It’s a book! Finally, after 8 years of research and writing, I finally have a finished first draft of The Trouble with Virginia. Yippee! Betcha didn’t think I was going to finish, did ya?! Now, on to revision. I’ll keep you posted!

It’s a book! It’s a book! Finally, after 8 years of research and writing, I finally have a finished first draft of The Trouble with Virginia. Yippee! Betcha didn’t think I was going to finish, did ya?! Now, on to revision. I’ll keep you posted!

A visit to Chellow just went onto my TO DO List.

Chellow. Photo Courtesy Virginia Department of Historic Resources

In 1936, Rosa G. Williams surveyed Chellow for the Virginia Historical Inventory. At the time, the house stood empty. The caretaker was a son of a former slave owned by the Hubbard family. Mrs. Williams wrote:

Chellow Plantation is part of a grant of 6,740 acres, originally in Albemarle County, now Buckingham County, Virginia. Patented to Colonel John Bolling, July 20, 1748. Chellow was named for an old English Estate of the Bollings.

The home is a very imposing example of colonial architecture, consisting of ten rooms. You must enter the front by way of a “T” shape hall, to the right as you enter is a large bed room, to the left is a large library or living room, to the center of this hallway is a door leading to a lovely dining room, with French windows, lovely old doors with…

View original post 310 more words

What a great document! So sorry to see none of my ancestors on the Colored list though 😦

Courtesy Bibb Edwards

In the spring of 1867, Lieut. Col. John W. Jordan provided Gen. Orlando Brown of the Freedman’s Bureau with a list of men, both white and African-American, whom he felt were qualified to lead the Buckingham County through the post-war Reconstruction.

Click here to catch up: Reconstruction in Buckingham County, Part I

Here are the names he provided:

White

Thomas H. Garrett, Curdsville

Thomas Leitch, New Canton

B. Finklin, New Canton

J. Bondurant, Mt. Vinco

John R. Gilliam, New Store

Dr. E. C. [Charles] Davidson, Court House

Colored

John Scott, Curdsville

Woodson Washington, Rock Mills

Cesar Perkins, Court House

Solomon Brown, Curdsville

John Stanton, New Canton

Peter Fontaine, New Canton

~

Lt. Col. Jordan had searched far and wide for evidence that these men been had not been in favor of the secession of Virginia from the Union, that they supported the new freedoms imposed by Federal…

View original post 76 more words

Put this on your reading list!

My husband walked into the house today with a heavy box from the University of Alabama Press.

My husband walked into the house today with a heavy box from the University of Alabama Press.

What was inside?

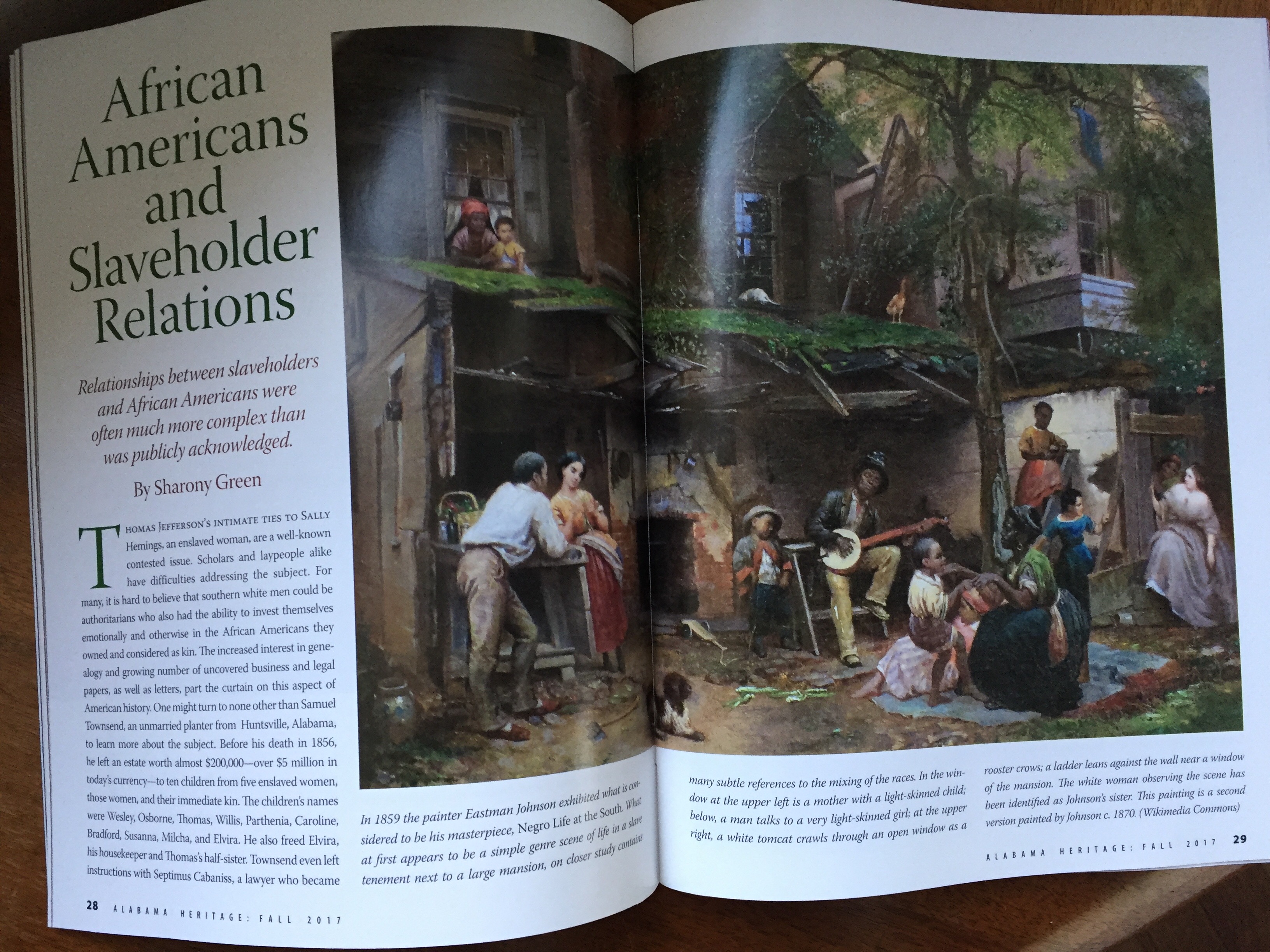

Several copies of the Fall 2017 issue of Alabama Heritage magazine. Among the stories is an article I wrote. The article concerns the historical actors in Remember Me to Miss Louisa: Hidden Black-White Intimacies in Antebellum America (Northern Illinois University Press, 2015).

The beautiful illustrations the magazine selected put on display our messy shared past. Among them are nineteenth century politicians like New York Senator William Seward and Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas and Alabama Senator Clement Claiborne Clay. All of these men were consulted about the best place to relocate the children from one Huntsville family who were freed by their masters, both brothers.

Telling of this mess – and by mess, I mean, among others things, that interracial ties, coerced or not, are as difficult to discuss then as…

View original post 116 more words

First It Was Slave Teeth for Dentures, Now Slave Hair for Furniture Stuffing

When I stumbled upon this recently posted video, it was not something I had ever heard of before. Posted on YouTube by Yisreael Ben Yehudah, the poster says he was restoring a 200-year-old chair for a client when he discovered it had been stuffed with slave hair. Slave hair?! Yep. See it for yourself. On top of the human hair is a layer of cotton. Well, we know who grew and picked that cotton. Looks like they contributed a lot more than the toil and misery of their labors.

Photo: Screen capture of Yisreael Ben Yehudah’s YouTube video

Granted, in that time people used whatever was available to stuff mattresses and furniture and the like–horsehair, cattails, moss hanging from trees, corn shucks, whatever else was handy. But I had never heard of slave hair! And the quantity of hair that is in this chair is mind-baffling. Painful. After watching his video, of course, my mind is running wild trying to imagine the circumstances of what that collecting of hair must have been like for the slaves. I shudder at the thought; it makes me think of antebellum sheep shearing day. But now, of course, I am driven to find out.

Teeth, Hair; What Else Don’t You Know about Slave History?

It’s no secret that George Washington probably had dentures that included teeth from slaves–it is documented that he purchased “9 teeth from ‘Negroes’ for 122 shillings.” (See number six on the list.) Now we can add hair to the list of usable parts harvested from a slave. And now I have a new topic added to my ever-expanding research list. Who knows–will this need to show up in my book? Thank you for sharing, Mr. Yehudah.

See Yisreael’s video here: 200-year-old chair padded with slave hair

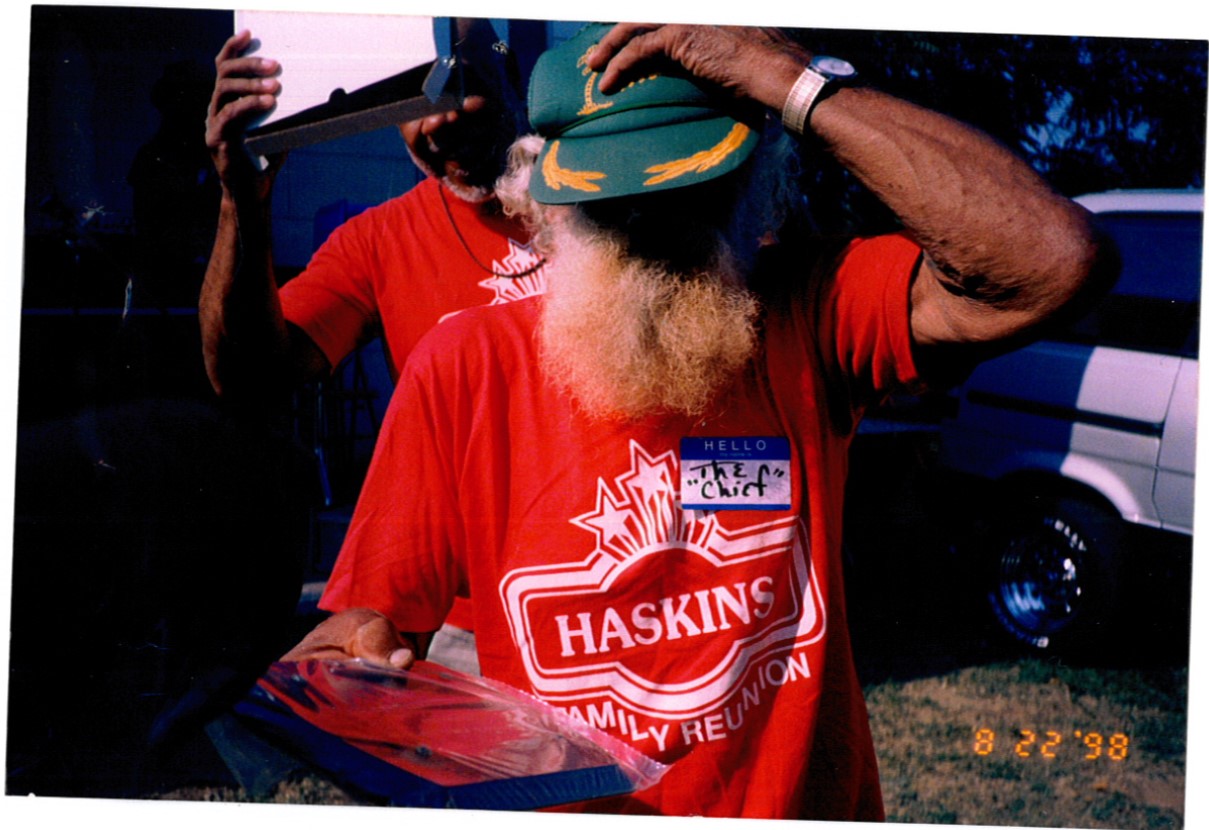

Meet my Uncle Wardie (“The Chief”), who inspired some of the traits of the crazy but lovable fictional character Ole Albert in the book. Cornelius Warden Haskins, born on this day, 1917, is my grandmother’s youngest brother, and the one who stayed back in Virginia while his siblings journeyed to Harlem during the Great Migration, the decades-long migration of black citizens who fled the South for northern and western cities in search of a better life. Actually, he did follow his siblings to Harlem but quickly realized it wasn’t for him and headed back to Buckingham County pronto. Carsue, my grandma and Wardie’s oldest sister (born February 2, 1897), was the first to leave The Homestead, third grade education and all. (More on the schools for blacks in another post.) You can see pictures of my Grandma if you head over to the Photo Album page.

Meet my Uncle Wardie (“The Chief”), who inspired some of the traits of the crazy but lovable fictional character Ole Albert in the book. Cornelius Warden Haskins, born on this day, 1917, is my grandmother’s youngest brother, and the one who stayed back in Virginia while his siblings journeyed to Harlem during the Great Migration, the decades-long migration of black citizens who fled the South for northern and western cities in search of a better life. Actually, he did follow his siblings to Harlem but quickly realized it wasn’t for him and headed back to Buckingham County pronto. Carsue, my grandma and Wardie’s oldest sister (born February 2, 1897), was the first to leave The Homestead, third grade education and all. (More on the schools for blacks in another post.) You can see pictures of my Grandma if you head over to the Photo Album page.

Wardie never married, never had kids. He kept The Homestead going, farming various crops and raising pigs for a living. And he scared the heck outta me every summer I went to Virginia as a young girl! Somehow, though, I adored him at the same time. I remember those childhood summers fondly. Uncle Wardie wheezed something terrible with his asthma and stunk to high heaven in his dirty coveralls that he wore every day and rarely washed. You could smell the whisky on his breath, too, and his beard was stained yellow from the chewing tobacco he spit out–the spittle that didn’t quite make it into the odious coffee can he kept near. He had a fingertip or two missing from a farm accident. “How’s my girl?” he used to wheeze and cackle as he would reach for me. Whenever he saw one of us kids headed for the outhouse behind the house (the same house that was built in 1850 for Virginia and Robert when they married), his face would crack impishly. “Watch out for them snakes!” he’d call behind us.

Happy Birthday, Uncle Wardie. Miss you. xo

I asked my uncle if he thought my grandma (his mom) or great-grandma would have been taught by any of these teachers…he mentioned visiting a one-room school in Appomattox, which he says would have been the closest school to our family homestead. The search continues….

Thanks to Joanne Yeck, at Slate River Ramblings, for her invaluable and immense knowledge of Buckingham County! Check out her blog and be ready for some fascinating history!

Courtesy Library of Virginia

Above is the 1894-1895 “Census of Colored Teachers,” listing the African-American teachers in Buckingham County. Note that there were considerably fewer African-American teachers (24) than there were White teachers (62) working in the county.

Members of the Lomax family of Buckingham Court House were leaders in Buckingham County’s education of African Americans. In 1894-1895, three of them were teaching at the county seat: Mr. Edward S. Lomax, Mr. E.W. Lomax, and Mrs. Josephine Lomax. Edward S. and Josephine Lomax were married. E.W. Lomax was their son, Eugene. By 1900, their son, Clarence, was also teaching school in Buckingham.

Mr. James B. Riddle of New Canton also appears on the census. He was the uncle of Dr. Carter G. Woodson and, in 1926, helped establish Liberty School. The two-room schoolhouse was located near Third Liberty Baptist Church in New Canton and was built at a cost of…

View original post 17 more words

Submit!

Share your story. We?re seeking filmmakers, writers, bloggers, performers and scholars of every stripe who have stories to share about the Mixed and multiracial/multicultural experience. We?re also seeking panel presentation ideas and workshops. The deadline is Jan. 18, 2016. There is no submission fee. Find out how to submit your work here.-Heidi Durrow, Festival Founder ?

Sourced through Scoop.it from: www.mixedremixed.org

3. (continued) (see here for the first part of this installment)

[Again, I am still awaiting copies of the original documents from the University of Virginia Library and will double-check the details — more later. The following information has come courtesy of what turns out to be a distant cousin on the white side, Bev Golden, who does have her hands on the documents. (See her link at the bottom of this post.)]

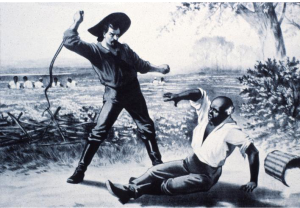

Murder in Buckingham County!

According to court testimony, Christopher beat Will “hard about the head” with a 4-5 foot hickory hoe, continuing to beat him even after he fell to the ground. He then ordered other slaves to haul him to the tobacco barn and lock him inside (evidently a common punishment for slaves in Virginia — see videos below to learn more about Virginia tobacco barns and the tobacco-growing way of life) and wouldn’t let anyone help him. It’s not clear when Will was brought out of the tobacco shed, but he died on a Tuesday, three days after the beating. But the tragedy doesn’t end there. Johnson patriarch Richard then had Will’s body brought into a slave cabin and laid out on a bed of straw. The straw was then set on fire and the body burned, apparently an effort to cover up evidence of the crime. Another interesting twist: based on the locations of the farms of the neighbors who offered testimony, it seems likely that the murder occurred at the father Richard Johnson’s plantation, not Christopher’s, suggesting that Will was owned by Richard and also explaining why Richard was the one who took action to cover up the crime. It would appear that Christopher was the overseer for his father, in this case. (Not yet confirmed.) It might also explain why Jack was present.

Above is the remains of an old Virginia tobacco barn. The (longer) video below gives a much better idea of what they were actually like, taking you on a tour of a barn in much better shape still today.

Johnson Disappears

The charge of murder was based not just on the fact of the beating as the cause of death (which could have been legally excused as an accident resulting from “justified” discipline), but from its viciousness and the fact that medical aid was denied for the several days it took for Will to die. One witness testified that Will was held “prisoner” before his death.

The Buckingham County Courthouse, pictured here in 1914. The original Courthouse, designed by Thomas Jefferson and built between 1822 and 1824, was destroyed by fire in 1869.

Interestingly, Christopher didn’t attend the trial; he had managed to escape from jail and by the time of the trial was nowhere to be found. Some of the testimony at the trial touched upon his current whereabouts, and it appears that he stayed in hiding in the local area waiting for the verdict to be decided. He was reported by one witness as having been seen near the courthouse (some miles from his farm), perhaps in an effort to learn what charges if any were pending. Christopher had previously given Will a severe beating earlier that same year. Johnson’s neighbor Joel Flowers testified that he first denied what he had seen, then admitted it because he “had been present when Denny was whipped.” This was probably a reference to William Denny, another witness at the trial–apparently Christopher whipped his neighbor Denny, too, perhaps in an effort to prevent him from testifying.

Christopher Johnson was convicted but was never recaptured, and he never returned home. By 1825 he had completely disappeared; his estate was settled in 1832. I found it also interesting to note that Richard Johnson’s September 1823 will made no reference to Christopher’s crimes nor his disappearance, leaving him a sum of money about the same as the rest of his sons (except Philip — more on him in a future post). Following are some (disturbing) excerpts from the trial notes:

“Commonwealth vs. C. Johnson – ch’d with murder”

The records that survive are horrifying and remarkable; testimony includes the following comments:

N. R. Powell (appears to be a doctor): “Many marks of violence — bones of nose broke — one eye out — small fracture in temple — found before he got to place — most (wounds) not dangerous — concussion of the brain most probable result — death proceeded without medical aid — slight inflammation of brain near eye — Inflammation not as great as happens where death ensues concussion — possible from all appearances that he might have died from the injuries all together.”

William Freeland: “saw Johnson at courthouse day of August, [posing?] about at various places, has reason to believe he would surrender himself.”

Reuben Johnson (another Johnson brother): “Heard on Sunday that Will was dead, Monday morning afterwards was making [tobacco?] hills — Tuesday night afterwards he died, Wednesday morning he helped make coffin and three negroes carried off the coffin, he heard knocking on coffin as though nailing it on, negroes carried coffin toward the grave –”

(See this National Park Service link for more on growing tobacco and an explanation of tobacco hills)

Jack Johnson (Virginia’s father, my 3X great-grandfather): “was at his Father’s the night Will died, a negro came to his Father’s from the new ground and said Will was dying, his Father sent for Will, he died that night. Saturday he was making tobacco hills and was complaining as usual, straw did burn and his Father got up about the fire.”

Richard Johnson (the Johnson patriarch): “same as to negroe’s being sick at new ground, put him in the house on straw, he was shrouded and straw and clothes burnt off of him, no marks of violence, negroe was healthy …”

William Denny (neighbor); heard [Smith?] say that he whipped negroe about meat [March? Or stolen meat?] and then gave him another whipping about [August?] a severe whipping to his satisfaction.

William Wright (neighbor): [blotted word], said he was inside of said Johnson’s plantation on the [mill?] hill, and Johnson on back part of his plantation, about half a mile off.

Joe Clark (neighbor): “heard Flowers speaking of distance and pointing to distance [east?] [& etc?].”

Thomas Wright (neighbor): “was at Johnson’s on Tuesday [that day stated?] Will died Johnson was from house and the headman beat him very much with a hoe he lay stick [& ea?] [stick down?].”

A Slave’s Murder in Buckingham County Makes the Front Page

After Christopher was convicted, a notice was published in the most prominent Virginian newspaper of the time, the Richmond Enquirer, on July 15, 1823, advertising for his recapture:

“By the Governor of the Commonwealth of Virginia – A Proclamation:

Whereas it has been represented to the executive by the jailer of Buckingham county that Christopher Johnson and James Smith, confined in the jail of the same county the first named, committed on a charge of murder and the last named for larceny, against whom a verdict was…

Christopher Johnson is about 50 years of age, six feet tall or upwards, stout made, rather corpulent, (stooped?) the shoulders, short black hair, (…) eyes, Roman nose, long chin, and a small puckered (mole?)…

For a longer version of the Virginia tobacco-growing life, take a peek at this video, courtesy of Preservation Virginia:

This information came to me thanks to my dear cousin John Haskins, who shared a posting on the site FindAGrave.com written by Bev Golden, which I paraphrase here. I’m glad to have met Bev. Her original source is from a collection at the University of Virginia Library archives, copies of which I am anxiously awaiting now. Here is Bev’s post.

Christopher Johnson’s defense attorney Walter S. Fontaine’s notes of trial testimony and his defense strategy are in a collection of his papers at the African-American Sources: Manuscripts Division Special Collections Department at the University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, VA:

319. FONTAINE FAMILY PAPERS: Business, legal, and personal papers of Colonel Walter S. Fontaine of Buckingham County and of the Fontaine, Brown, Thompson and allied families. There are … and testimony from relatives and neighbors regarding an accusation that overseer Christopher Johnson beat a slave to death. Reference: (Acc. 4149)

3.

Here, at long last, is the third installment on the story of my arrival at the subject for this book. I have been busy in the archives–wow! What things I’ve found! I think my head might burst open, it’s so full. So many posts now I need to share with you. My book project keeps growing. I hope after you read this post you will understand the reason for my tardiness in posting. I am still awaiting copies of the original documents from the University of Virginia Library and will double-check the details — more later. This information has come courtesy of what turns out to be a distant cousin on the white side, Bev Golden, who does have her hands on the documents. (See her link at the bottom of this post.) If you’re new to this blog, back up to the previous two posts to catch some background on who is who so I don’t confuse you. So, without further ado, let’s go. Put your seat belts on.

July, 1823: That’s the Night Month the Lights Went Out at the Johnsons

1823 was an eventful year in Buckingham County, Virginia, at least for the Johnson family. For one thing, Johnson patriarch Richard, father of my great-great-great grandfather Jack, penned his Last Will and Testament on September 8th (read more about it in my last post, “And So the Search Begins,” May 16, 2015). Also, although this wouldn’t have anything to do with the Johnson family until his wedding in 1850, Robert Haskins (my great-great grandmother Virginia’s future husband) was born, chattel property of the Haskins family who lived nearby. Another notable event during the summer of 1823: Jack’s brother Christopher became rather notorious in the neighborhood for a heinous act against a slave — even to the whites.

The Master Shall Be Free of All Punishment

Virginia was a state in which it was almost impossible for a slaveowner to be charged with murder in the death of a slave; the colony of Virginia had established a tradition regarding the treatment of black slaves all the way back in 1705. In that year, the Virginia General Assembly made its position quite clear on the status and rights of black slaves, with a declaration that would help establish the brutality of slavery for many future generations: “All Negro, mulatto and Indian slaves within this dominion…shall be held to be real estate. If any slave resist his master…correcting such slave, and shall happen to be killed in such correction…the master shall be free of all punishment…as if such accident never happened.” (See this PBS link for more on Virginia’s slave codes.) Despite these slaveowner protections against the torture or killing of a slave, during the summer of 1823 — months before patriarch Richard wrote his will — Christopher Johnson was indicted for murder in the beating death of a seventeen-year-old black man, chattel property of the Johnsons, a slave named Will.

Surprisingly, Christopher was not just charged with the murder of young Will: he was ultimately convicted. Most interesting is the fact that his conviction was based on the testimony of his very own white neighbors: they were apparently scandalized and incensed at the level of Christopher’s brutality toward another human being, black or otherwise. This might suggest that Johnson had already earned quite a reputation amongst his neighbors for some pretty savage behavior toward his enslaved brethren (and maybe his white ones as well–more on that later). The fact that Christopher refused to allow the local doctor to be sent for and also refused to allow other slaves to tend to Will after the beating helped convince the Court that the slaveowner had intent to harm or kill, a factor which worked against him despite the protections of the Slave Codes. At the trial, a neighbor, Mr. Pankey (possibly a doctor but I haven’t yet confirmed), testified that none of Will’s wounds should have been fatal, and that he believed Will could have been saved if a doctor had been allowed to provide medical care. Left to suffer in solitude, it took three long days for Will to die, locked up in a hot, stuffy tobacco barn.

From the court records, it appears that 45-year-old Christopher became “enraged” at 17-year-old Will while the young man was working a new tobacco field. A disturbing note for me is that my white great-great-great grandfather, Jack, appears to have testified in support of his brother during the hearing, with a statement that Will was “complaining as usual” that day. Did Jack witness the horrific beating? Did the notion of Will “complaining” make it okay to beat the young man senseless (actually, beat him to death) in Jack’s mind? Jack, whose own children were mulatto and legally his slaves? (Who openly lived with their mother, also mulatto and slave?) This new information forces me to re-think my understanding of my ancestor Jack Johnson. Historically, Julys in Buckingham County are hot ones, averaging in the 90s. (weatherunderground) I try to imagine what it must have been like for 17-year-old Will, enslaved, probably underfed and hungry (based on details from the testimony–see next post), and out in that hot field with an apparently already angry white man who was probably the son of his owner (Richard), overseeing his every move and (apparently) accusing him of stealing meat. But. One must ask: was Will that much of a rebel? Or does this speak to the general attitudes of the Johnsons about their slaves? Perhaps it’s a little of both? (Much more on Jack in future posts.)

Stay tuned for the second half of this long post, coming Monday!

This information came to me thanks to my dear cousin John Haskins, who shared a posting on the site FindAGrave.com written by Bev Golden, which I paraphrase here. I’m glad to have met Bev. Her original source is from a collection at the University of Virginia Library archives, copies of which I am anxiously awaiting now. Here is Bev’s post.

Christopher Johnson’s defense attorney Walter S. Fontaine’s notes of trial testimony and his defense strategy are in a collection of his papers at the African-American Sources: Manuscripts Division Special Collections Department at the University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, VA:

319. FONTAINE FAMILY PAPERS: Business, legal, and personal papers of Colonel Walter S. Fontaine of Buckingham County and of the Fontaine, Brown, Thompson and allied families. There are … and testimony from relatives and neighbors regarding an accusation that overseer Christopher Johnson beat a slave to death. Reference: (Acc. 4149)

A blog about Saabs & Saab Culture

Black Knowledge Queer Justice

A selfish poet

Define Yourself for Yourself!

Empowering women writers to submit their work for publication

the dots are there - i just connect 'em

Everything Virginia history!

A blog by Tim Carl

This WordPress.com site is the bee's knees

Being in gratitude

One Woman's Quest to Become a Writer

Seasonal Vegetarian Recipes & Lifestyle Ideas

This site is devoted to the aesthetic appreciation of abandoned and decaying old homes and other buildings and such, and is the official companion web site to the wildly popular Abandoned in Virginia page on Facebook.

A Biracial Swirl in a Black and White World

creating a bye-racial world

In the life of a Biracial Girl . . . my truth in Black & White.

Society for the Study of American Women Writers